In school, I was never good at defending where an idea came from, or worse, my choice of media. In high school & college, I chose to work digitally because I knew the tools, not because it added to the work, much to my art professors’ disapproval.

In school, I was never good at defending where an idea came from, or worse, my choice of media. In high school & college, I chose to work digitally because I knew the tools, not because it added to the work, much to my art professors’ disapproval.

Now that I spend much of my free time drawing, I still believe in the importance of arbitrary choice. I’m a firm believer in odd dimensioned paintings (that fit in the car, for transport to shows) or drawing on fabric caught on an embroidery hoop (to create a scroll that wouldn’t need to be framed, and so avoid the upfront cost of framing), or choosing to work small, because it’s easy to transport, and I can work on it on my lunch break. All arbitrary reasons that make art making accessible.

Integrating life and art leads to odd juxtapositions. I don’t know how long I’ve spent staring at the olive trees on my lunch break–the twisty roots, and sensible pruning–and learned to “see” them from drawing.

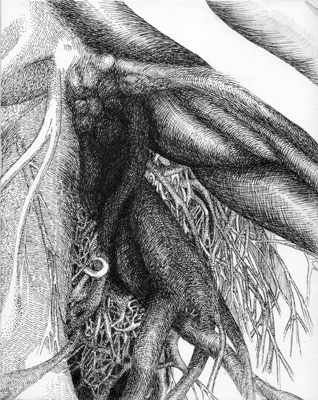

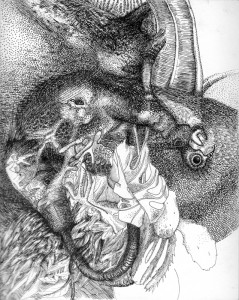

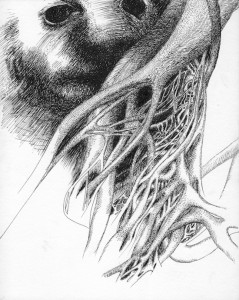

Let me show you the olive tree from my office park:

Did you notice the whale?

It’s the best part, but it wouldn’t have happened without the olive trees.

Let me show you how it got there.

How The Whale Joined The Olives

Three years ago, Richard Boyle, a scientist who studies “the ear in space” gave me cross section photographs of the little pockets of hairs in the inner ear. My initial drawings looked like tiny wrigley stalagmites, and I put them everywhere.

I drew those hairs so many times, and so many places they didn’t fit, that they stopped being patterns, and started to become tube worms, and anemone arms.

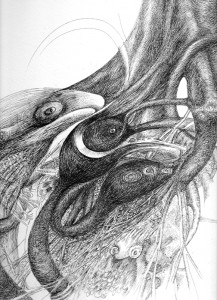

Then the fish appeared.

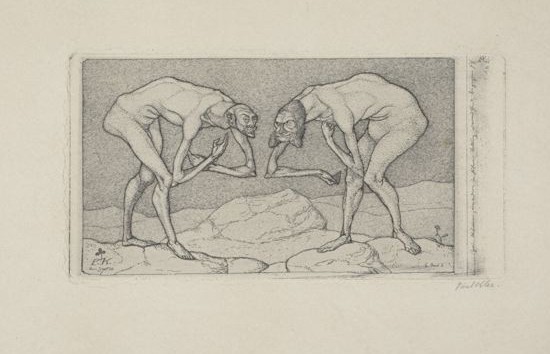

- Grouper, pen & ink McNamara 2014

I got a new job. At my new job, I quickly began to choose my parking spots based on the view. Which olive tree had the knobbiest roots? And, for a bit of practice, I drew olive roots at lunch.

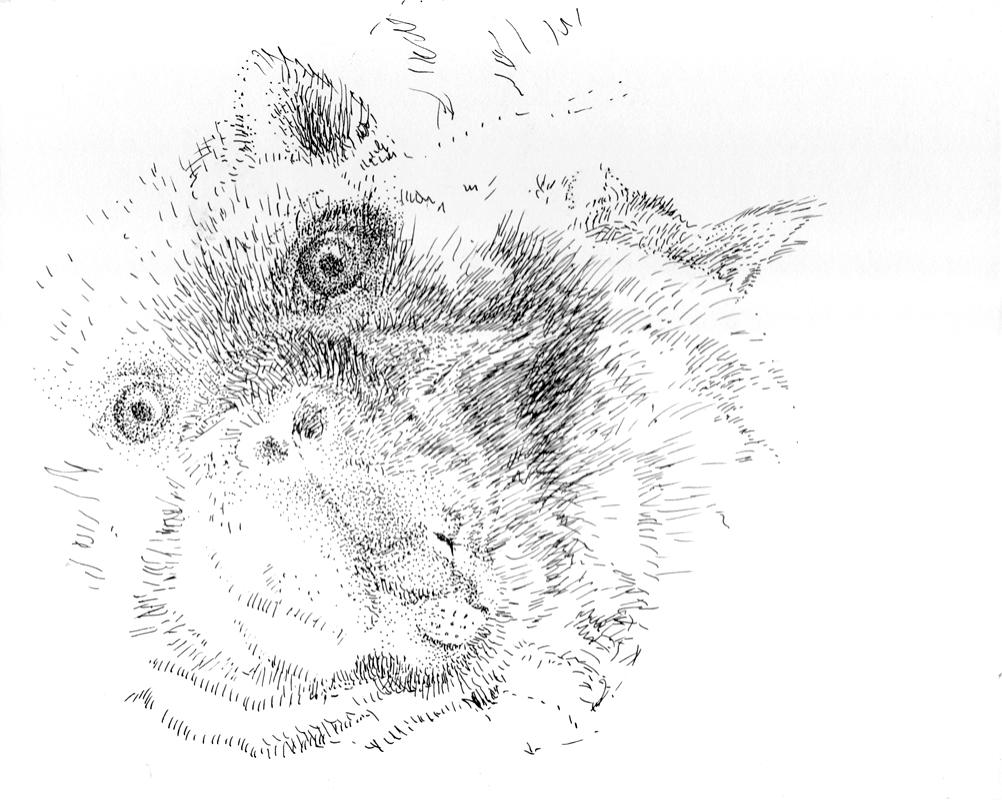

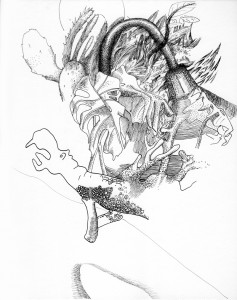

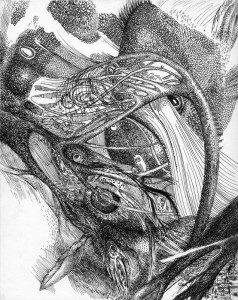

When my olive roots were no longer exciting, I slid the work to the end of the stack of “work to do” to protect it from the wastepaper basket. In the meantime, I drew, with no composition, sketches of things I saw, on a piece of paper I was reluctant to change while white still remained. Here it is in its early stages:

Sea Creature In Progress, Seana McNamara, October 2013

Notice the hippo figurine, the desk lamp, and the houseplant?

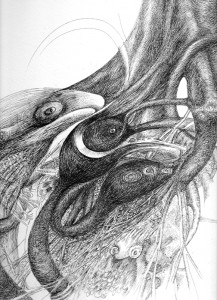

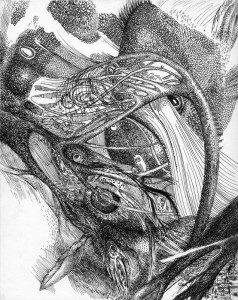

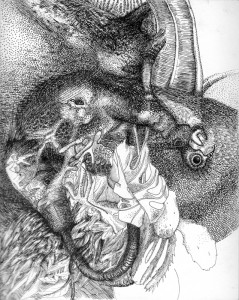

It became this:

Sea Creature, Seana McNamara, February 2014

The “stuff” now has character. They’re creatures I’d like to meet. From the top left, a newt like creature is swimming into the frame and in the middle, a large jawed creature with a small eye is doing his best to turn into a piece of coral. Why not?

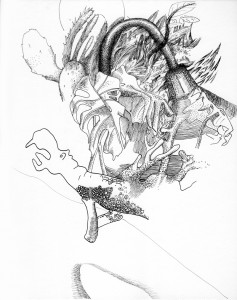

My newt, sea creature, and coral combination had enough life that I accepted that my ocean creatures could exist in their own right. So, when two lines and a few scribbles on my olive roots reminded me of a whale, I was willing to run with it, rather than shelving the drawing.

Ideas that appear spontaneously are worthwhile. Most of us accept evolution in science, and most of us don’t discount how well put together a bird looks, just because the depth of his beak wasn’t a premeditated decision. (Must have a bigger beak now!) The bird is a coherent whole, even if his anatomy developed piecemeal, over the lives of many many birds. It’s the same with ideas in art.

If I were to create work that was just for me, which no one else ever saw, then creating a visually arresting object would be enough. But as soon as I show the work to someone else, they want a logical context for the work. Not that logic wasn’t at work before, it was just logic over time, iteratively, a very different kettle of fish. And no one’s interested in dealing with lots of little fish, when they could have one large fish instead. Why have several tangential explanations, when you could have one? So out comes the fish compressor and hopefully what results isn’t the pacific equivalent of a meal of compressed chicken (my feelings when reading artist statements).

But Where Did Your Idea Come From? It’s not that the person asking the question really wants to know where it all comes from–they just want a compass to get their bearings. From my point of view, they want the biggest arbitrary decision, from which all other decisions flowed logically. The premise.

It started with an ear.